Pessimist or Realist? A Conversation with Scott Galloway on the Future of Everything

- 0.5

- 1

- 1.25

- 1.5

- 1.75

- 2

Michael Rivo: Welcome back to blazing trails. I'm Michael Rivo from Salesforce Studios. Today we're going to be talking to none other than professor Scott Galloway, about a wide range of topics, everything from higher education, vasectomies, yes, vasectomies, what industry he thinks the next billionaire will revolutionize, and what companies should be thinking about right now. But before that, I'd like to introduce you to Shannon Duffy, EVP of marketing here at Salesforce, to talk about our upcoming connections of inaudible which is Salesforce's conference aimed at marketers, commerce professionals, and digital professionals in general. Welcome to the show Shannon.

Shannon Duffy: Thank you, Michael. I am so excited to be here.

Michael Rivo: Shannon in the upcoming conversation, Scott talks about the great acceleration, which he describes as a decades worth of digital transformation happening just in a little more than this past year. This has created a lot of issues for lots of companies. What are the top issues that you're seeing today for marketers, e- commerce professionals and just across digital in general?

Shannon Duffy: It is the most exciting time to be a marketer, and there are so many things that your marketing or CMO, your CDO, your digital professional has to keep up with right now. We were at the tip of the spear. I'm a marketer, so I can say that, around driving growth for our businesses during a time of immense change in the pandemic. Everything was digital marketing, and digital marketing was the way we were connecting with customers. Now, as we start to see the light at the end of the tunnel, we are still grappling with what is the new normal and how do we connect with our customers in the best way possible, to be that growth driver for our business. That's just something that's top of mind for every single CMO, CDO, digital chief growth officer that I talk to this days.

Michael Rivo: There's a lot we've been talking around elevated customer expectations, which I think was happening before the pandemic, for sure. But now every business needs to be digital. Every business needs to offer a whole new set of ways to connect with their customers. Not only through marketing, but through product and across the board. How are you going to be talking about that at the upcoming event, and what can folks learn?

Shannon Duffy: Customer experiences is going to be core to everything. We talk about connections, and more importantly, we're going to show you how to build them, actionable tips that marketers and CDOs can take away to drive this in their business.

Michael Rivo: Fantastic. Give us the details. When is it? How can I sign up? It's free, right?

Shannon Duffy: It's free. It's free. Connections is free. All this learning, all this great networking, all this entertainment free, free, free. Sign up. It is June 2nd 9: 00 AM. Go to salesforce. com/ connections. Sign up. You'll get some updates. We'll give you all the great followup content. You will have links in the show notes it looks like, I don't know. Michael, tell them where else they can find connections.

Michael Rivo: Just to say it again. It's June 2nd 9: 00 AM. Pacific time.

Shannon Duffy: I'm so excited.

Michael Rivo: I know. It's going to be amazing. It's very simple. Salesforce. com/ Connections. Go there, you get all the information, and yes, after the show is over, there's going to be a podcast extravaganza with all kinds of great content, and it's going to appear on two shows that we have. One is called Marketing Trends. The other is Up Next in Commerce. As you can imagine, the marketing trends show is for marketers, and the Up Next In Commerce is for commerce professionals, so we're gathering all the best content from connections, and going to be running special episodes inside of marketing trends and commerce. You can find those links in the show notes.

Shannon Duffy: I love it. You can learn from anywhere. Podcasts from anywhere.

Michael Rivo: That's it.

Shannon Duffy: Going for a walk, learn about marketing.

Michael Rivo: Shannon, thank you so much for joining today.

Shannon Duffy: Thank you, Michael.

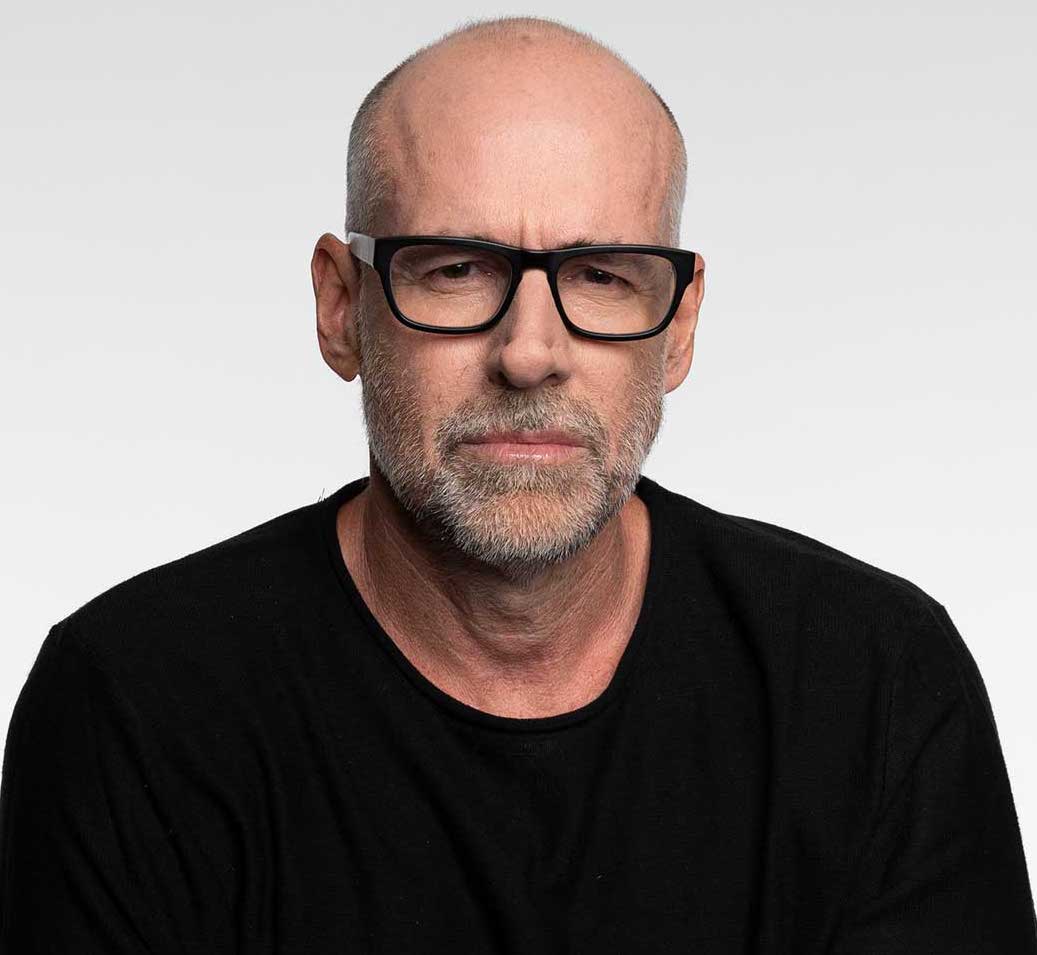

Michael Rivo: Okay, wonderful. Now, let's get to my conversation with professor Scott Galloway and Salesforce's VP of customer insights, Karen Mangia. Hey, welcome to Blazing Trails. Today, we've got Scott Galloway, professor of marketing at NYU Stern, founder of L2 red envelope, profit and section four. He's a best- selling author and host the prof G show, and he's cohost of Pivot with Kara Swisher. Welcome to the show, Scott.

Scott Galloway: Thanks for having me.

Michael Rivo: All right. Also joining me today is my friend and colleague Karen Mangia. Karen is vice president of market insights at Salesforce and is author of the fantastic and timely book Working From Home. Karen, welcome.

Karen Mangia: Thanks so much. Great to be here.

Michael Rivo: Great. All right, let's get into this. Scott in your latest book, Post Corona, From Crisis to Opportunity, you dig into digital transformation and boy, we've been hearing a lot about that just about everywhere, but you've got a unique take that you call the great acceleration. Can you tell us a little bit about what that means?

Scott Galloway: It's not anything that novel at this point, but if you think about how we as a species or as man perceives time, we think of it in relationship to these astrophysical objects, circling a spherical ball of hot plasma, or specifically 24 hours. That's how long it takes one object to circle another. But really, time as we reference it or as we absorb it is a function of change, so by that standard, you've had a decade of acceleration. E- Commerce was at 18% of retail, growing 1% a year in 2020, within eight weeks post April, it shot to 28%, so we had a decade of acceleration in e- commerce. Home delivery of grocery, working from home, parents living with their children, government spending, everything seemed to accelerate anywhere between three and four years and 20 years. This will be the enduring feature of COVID-19 or its enduring impact will be seen as an accelerant more than a change engine.

Michael Rivo: How permanent do you think some of these changes? Nobody can really tell, but what do you think is the stuff that's going to stick?

Scott Galloway: It's situational. If you think about the work from home, if you speak to somebody who owns an office building, they're convinced that everything's going to go back to the way it was, and it's not. The building I worked in right out of UCLA 1251 out of the Americas when I worked in the analyst program at Morgan Stanley, they track the number of people in the building for security purposes, and it averages 8, 500 people during an average weekday. It's now 500 people. It'll come back, but it's not going back to 8, 500. If you take out all the real estate, commercial, retail, and residential, you take out residential, you have a$ 12 trillion asset class, and it's conservative to say, you're going to see a gross demand destruction of 20 to 30% across retail and office, or you're talking about the GDP of Japan being dispersed if you will, or transferred from office space to residential. You're going to see office rates in the office industrial complex, these restaurants that serve them get hit hard, and then the brands that serve you in the home, whether it's William Sonoma inaudible or Sonos, are going to accelerate, and we've already seen massive increases in pricing and housing and housing suppliers. I would argue, and that's one of the things I ask the management team when they tell me about their business, and I say, “ Well, are these changes cyclical or structural?" If you're doing well, you want to think that they're cyclical, but usually they're what I call two third structural. Sure restaurants will have an easier time moving forward, we're probably going to lose a third of restaurants by name. There's just a different view of restaurants now, and there will be a different ecosystem for the winter. I think most of it is enduring most of the changes.

Karen Mangia: Scott, when I hear you say that the acceleration factor, I think about what's happened in the context of customer connection, and I think about so many businesses that I have conversations and visit with, that have these digital transformation strategies and customer experience strategies. In an ideal world, those are connected. What happened was everyone accelerated into a simultaneous pressure test that said how awesome or not, or how effective or not are those two strategies. What I've observed in some of these conversations and experienced, is the sunlight shines through the cracks of where that strategy isn't entirely seamless. I think about what happens when some of those ways that businesses first engaged customers to create that brand impression, evaporated. There is no waiting in the lobby. There is no moment where someone was physically coming into your space to intersect your brand, or couldn't connect with someone in person to answer a question. What I think about is, as people identified where those gaps were, they also came up with new ways to connect with customers, offer support, extend the brand promise, and now you can't step backwards from that line. You can't say, “ Well, we had this grocery delivery or this order ahead, but now we're going to take it back." People expect that, it's renegotiating. I think what we expect from colleagues, from companies, from brands, as we move forward.

Scott Galloway: I agree.

Michael Rivo: It makes me think about what this means for relationships with one another. We have a brand level with companies, relationship with customer, relationships with companies and employees. It just seems like it's going to be fundamentally different. I know for myself, having been away from people for so long, and then having to try to reconnect and sit down for a dinner and just do stuff like that, it's different, and takes some getting used to. Scott, how do you think companies need to think about the relationship with customers, etc, in this new world? It was digitizing anyway, but is this going to be a significant difference if you're not going into a store anymore, if you're not having those physical experiences? How's that going to change?

Scott Galloway: I think it's situational. The relationship between a movie theater and the end consumer is just much different than it was now, or the relationship between content and the end consumer. I would say the majority of the change, if you will, if you're trying to figure out, answer that question for your business, and you map out the supply chain and ask yourself who can be leapfrogged. Wonder woman, 1984, coming to your theaters or coming to your home is leapfrogging the supply chain of theaters. It used to be a key part of the supply chain. Working from home, renting your human capital to an organization without the supply chain of an office, is a key shift in the supply chain, whether it's Amazon moving to your driveway versus the store, there's just fundamental changes or shifts in the supply chain roadblocks saying, we'll let kids decide what games they want to play, instead of game houses or game developers. I think it really depends on the industry you're in, but I think it's a useful exercise to go through and say, all right, who comes up with the idea, who manufactures it, who designs it, who merchandises it, who distributes it, who retails it, who serves it or provides the customer service. Then what you're seeing very crudely is the guys or girls in the middle, are getting leapfrogged by usually companies to leverage technology, to provide more margin to the source of the value, or to make the end user experience more seamless for the end customer or client. It strikes me that it's this massive disruption in supply chain. Less than 1% of doctor's visits where virtual pre pandemic. Now, it's 32%. That might go back to 20 or 25, but that'll still be a 20 fold increase, and it's going to open up all sorts of opportunities and investment that will make delivery of healthcare to your smartphone, to your smart speaker, to your living room, to your kitchen. The reality we'd always talked about. It was supposed to happen, it never did because there's a lot of entrenched interests. It really depends on the industry. Some industries will feel fairly unchanged, and others are going to go through I think a dramatic of people, including my own in education.

Karen Mangia: What I hear you saying, Scott, I can resonate with in terms of, I think about it as the big impact question that so many organizations are asking now, and that big impact question is, who is our customer now? In so many industries and for so many organizations that shifted from a supplier or a distributor who perhaps sat between you and your end customer or student or person you served, or vice versa. It's that rethinking of the value chain. I think it's stepping back to consider for so many organizations within that big impact question about who is our customer now? Really, who do we serve, why do we serve, and what's the greatest good that we're expecting to deliver from that service? Your comments and statistics there about the healthcare experience reminds me of a big global health care organization I've been doing some work with, and they're trying to drive home this inflection point, about how the experience shifts when a patient and a doctor are interacting virtually, and to try to drive home and reconsider and reinforce this new sense of purpose and service, and the greatest good that could be delivered. They changed their tagline to, the patient will see you now. We're also accustomed to the doctor will see you now, but shifting that mindset of service, and that mentality of who's first and the order in which that value chain delivers, and who's in it, and really a shift in the critical moments of that experience, whether that's healthcare or education or a business like Salesforce.

Scott Galloway: Healthcare is an interesting one because who the end customer is, or who is a constituent that the majority of innovation focuses on is a key question. For example, the case of Facebook, the person using Instagram, the person on Facebook, isn't the consumer, that's not who they're trying to add value. They're trying to add value to the advertiser. They'll engage in surveillance capitalism, try and figure out a way to keep you engaged, even if it's not good for your mental wellbeing, even if it violates your privacy. Because at the end of the day, they're trying to please the advertiser with more relevant targeting and advertising. The health complex or the medical industrial complex, I think began servicing the insurance company. Trying to get optimal reimbursement, or trying to figure out how they got more money out of Medicare. It was basically the entire ecosystem got shaped around the supply chain, as opposed to the supply chain getting shaped around the consumer. A mother who's managing her child's diabetes spends 12 weeks a year managing that child's healthcare. Let's be honest, it's always a mom. If you think about the amount of time she's spending, it's okay, I got to drive to the doctor's office, I got to wait in a waiting room because we want to optimize the doctor's time, not the patient's time. He or she has to get, the mother has to get a referral to a specialist, because God, we don't want to spend money unless the doctor says you have to spend money here. She goes home. She gets another appointment, terrible appointment, not Google calendar. It's calling someone and being put on hold and telling you, I have an appointment in seven weeks, and you're saying, " Well, no, my child has serious asthma, or whatever I need to get in sooner." We'll call back in an hour. Back to the specialist. It's just so broken. Healthcare right now, I think everything is as retail. Healthcare is the second worst retail in the nation, and the worst is gas stations. I think our first trillionaire is going to be someone who figures out a way, not only to save money, but to save time around healthcare. Under the auspices of TMI, I'm 56, and I'm thinking about closing up shop and getting a vasectomy. It's taken me four months to get a second appointment. I did a consultation, I'm like, why am I here? So the guy can tell me what he's going to do to me? This should have been done over the phone, and I should have gotten this done the next day. Instead it's all this, just time on time, on time on calling them back, and then I even forget what... It's like, what is the point? We spend more money. The healthcare business is a$ 3 trillion business, and if you get really sick, and you're really rich, it's the best in the world, because you can get to the best specialist, best pharmaceuticals, best treatment. For everybody else, it's a Hyundai for the price of a Mercedes. Not even a Hyundai, It's a Hugo for the price of a Mercedes. I think there's just enormous opportunity. If I were a 25- year- old and just an economic animal, I'd want to place myself in between healthcare and technology right now. I think it's going to be a fantastic sector for the next 10 years.

Michael Rivo: Scott, you've talked about this idea of the brand age, giving way to the product age, which we're talking about product development in a way and supply chain, etc. Tell me more about that idea. I wasn't sure exactly what you meant by that.

Scott Galloway: Sure. If you think about how the economic Titans of yester year made a lot of money, or create a shareholder value is loosely what I call the brand age algorithm, and that is let's produce a mediocre product, a mediocre car, a mediocre salty snack, a mediocre beer, a mediocre shoe, and wrap it in these unbelievable brand codes. Use excellent superiority, European excellence, masculinity, hot, sexy. These things by drinking this soda, I felt a Reverend by driving this car, I felt elegant by using this hand soap, it made me feel more sophisticated. These were outstanding associations wrapped around oftentimes mediocre products that resulted in 30 cents of peanut butter paste being worth$2 because choosy moms choose Jif, and you're a bad mom if you don't buy branded peanut butter, and that it was a license to print money. The P&G's of the world, the General Motors of the world just were economic Titans. Then, with the introduction of Google, I think people pierce the veil and said, if I find the best product, a brand is really shorthand or a weapon of mass diligence. It helps me get to the right product. When I used to travel to London on business, which I did six, 10 times a year, until a couple of years ago, I would stay at the Four Seasons or the Mandarin Oriental. One, because someone else was paying, and two, because those brands always delivered a seven or an eight out of a 10. They're just very good at what they do. But then I started using TripAdvisor, My Social Graph, Google, Instagram, and I found that there's a small boutique chain of hotels called the Ferndale Hotels that were what I wanted. I want to hang out with people younger and cooler than me, because it makes me feel younger and cooler than I am. I want an ice jam. I want a certain aesthetic. I want a smaller hotel. I want a hipper feel. That's what this brand delivered against. Now there are so many weapons of diligence in addition to brand. There used to be this ocean of unknown, that the brand was a vessel that got you across. Nike was always going to deliver a decent experience. Instead, you have these bridges now called Google or TripAdvisor, or your Social Graph, so great products get heard now. Great products without marketing used to be a tree falling in the forest, but if you have a vastly superior product, word gets out. We've seen a reallocation of resources out of what I'll call traditional marketing, trying to create these brand codes or awareness into the product itself. Now, it doesn't necessarily have to mean just the specific item itself. It can be the way that it's delivered. White glove installation, or customer service it's outstanding. But there has been a reallocation. An example is Apple. Apple took$ 7 billion out of traditional brand- building and put it into the stores because the experience of buying an iPhone is what makes an iPhone so great now, or it's going into that story thing. I just love this brand, and when I heard of this brand. That's part of the experience and part of the brand. I think there's just been in some, Don Draper has been drawn and quartered. The advertising industrial complex is collapsing on itself. If you're watching a lot of commercials, it means your life hasn't turned out that well. Advertising has become a tax that the poor and the technologically illiterate have to pay, and it's business. I think the brand era, I think the sun has passed midday on what I'll call the brand era, which is what I proselytize for 25 years. I'm like, product doesn't matter. It really doesn't matter that much. Product quality is tapped out, and then digital unlocked all this incredible innovation around product.

Michael Rivo: I was going to say about those dollars that were in traditional TV, have moved to digital. It's still advertising. That model you see Instagram and Facebook, they're still growing. I was curious what your take is on Apple's new privacy features, and what the impact is going to be on marketers there.

Scott Galloway: Google doesn't serve me opioid induced constipation Ads, because I'm not searching for opioid induced. Google goes right to the bottom of the funnel and you identify, you say, " I'm in the market for a BMW three series." It says, " Okay." Then it says to Audi, " Would you like to run an Ad against this guy?" Audi says, " Yeah, absolutely." And Facebook does the same thing. What they've done is they've taken advertising and made them much more relevant, and now they're at 80 cents on the digital dollar, Amazon it's at 10. Basically the dirty secret of digital marketing is it's a terrible business unless you're Amazon, Facebook or Google. You might as well be in the yellow pages business. It's probably declining faster than the surviving yellow pages. Anyways, Apple versus Facebook, I love it. Mark Zuckerberg, doesn't like Tim Cook because he sees him as a scold talking his own book. He wants it to be a paid eco system, where people don't endure Ads, they pay for apps because Apple gets 20 to 30% commission on anyone that buys an app. He is talking his own book. He is being a scald. I think Tim Cook doesn't like Mark Zuckerberg because Mark Zuckerberg is an awful person, and a sociopath, but I absolutely love it. So far the evidence shows that 95% of people are deciding not to opt into Facebook's to when Apple says, " If you want to have this app track you across other sites outside of the app, click here, it's an opt in thing." That's really where they put the spear in their heart. It's not opt out, it's opt in. When you think about it, this is how, the thing that's going to hurt Facebook is this scrutiny this is bringing. I think a lot of Americans didn't realize, " Wait, Facebook is tracking me when I'm not even on Facebook. They're listening on my conversations, they're watching what websites I go to even when I'm not on Facebook." I don't think a lot of people realize that. I just think Facebook is totally defenseless here because what's their defense? Their defense right now is well, a lot of people don't want to pay$1, 200 for a phone. A lot of people are willing to make that trade off, and there are. There's a large audience of people that will continue to watch TV and endure the Ads because they want it for free. Even though arguably, they're not getting for free, they're paying for the cable, but Tim Cook's response is let people decide. Fine, if they want Facebook and they want you to serve Ads, and they want to continue to get it for free, all I have to say is, yeah, I'm opting in. I think this is really interesting and it also shows a key feature of the companies that have gotten above a trillion, and that is a market cap, and that is a vertical, they control the end distribution. What you're seeing is, Facebook is vulnerable because they don't control the end hardware, even really the end operating system, because some people would say Facebook's an operating system, but if a billion of the wealthiest consumers in the world, which is what iOS is, its the aggregation of the billion wealthiest people in the world. They can turn off Facebook, or they can basically kneecap Facebook, and that's Facebook's vulnerability, that's Netflix's vulnerability, that's Disney's vulnerability, is that they don't control the end distribution.

Michael Rivo: Facebook tried to make a phone in 2009.

Scott Galloway: As did Amazon.

Karen Mangia: It's like customers are almost faced now with a different set of trade- off decisions. As companies are navigating all this, it's really about price and personalization, but it's also about privacy and preference. What am I willing to give you? What am I getting in exchange for that? How much am I willing to pay? To your point, how much is my time worth? A pretty radical shift in terms of thinking about the value of a customer or the value of a company, or how that value exchange looks, and what makes that transaction or interaction or relationship between a customer and a company worthwhile.

Scott Galloway: You guys are essentially B2B company, and B2B is just a better place to be. B2C is so competitive. If you want to get consumers to take out their credit card and enter into a recurring revenue relationship, their benchmark is Netflix, and Netflix gives them a billion dollars of content for every $1 a month they spend. That's what consumer... Look at what Amazon offers. Amazon offers just 48 hour free delivery, photo storage, great video, Amazon music, all these things for$ 12 a month. That's what the consumer, that's the benchmark to get a consumer to enter into recurring revenue relationship. Whereas with organizations and corporations, they're much more promiscuous with their spend. If you can add any value or create something that strengthens their relationship, they'll spend hundreds of thousands or millions of dollars. I've always thought B2B is not as romantic, it's not as sexy, but it's a much better way to build a business or make a living.

Michael Rivo: What's interesting in the context of brand conversation, is so people use our products of marketing cloud product, for example, for B2C activity. How do you stand out against billion dollar spend of Netflix and etc, because there is the opportunity with a better product and social, etc, ways to reach an audience. But, how do you compete? How do you do that if you're a smaller company? How do you break through?

Scott Galloway: I'm not sure you can. I'm not here with a message of hope. I think these companies need to be broken up. I speak to boards all the time and the number one question I would say is how do we compete? If it's a retailer, how do we compete with Amazon? I say, “ You don't, you can't." If you look at Amazon over the last 20 years, they took a dollar from the consumer and they reinvested$ 1. 03, and every other retailer gets$1 and can reinvest$ 0. 83 because their investors want EBITDA. People can be remarkably innovative when they're told here's an infinite supply of capital and you just have to break even. It's not as if these retailers are stupid, it's just the fundamental shift in our economy as it relates to these disruptors, is there a boxer afforded 100% pure oxygen, and their competition, which where they have shareholders that have still demand profits. Amazon has convinced their shareholders to replace profits with growth and vision, and their shareholders have said, " Fine. Just keep growing, keep innovating, and we'll keep giving you a cheap capital." Almost every other retailers in that position, they get 83% pure oxygen, and if you're a boxer, you can be a better boxer. But if the other guy's getting 100% pure oxygen and I'm getting 83%, at some point, he just needs to land a blow and I'm going down. That's where you're competing with Amazon. I won't even say the term compete. They have such access to cheap capital, they have different standards to meet for their shareholders. They have overrun Washington. There are more full- time lobbyists working in DC for Amazon than there are sitting US senators. Facebook has more people in PR and Comms, spinning and manicuring. Mark inaudible I mentioned there are, then there are reporters in The Washington Post. The Toronto globe and mail combined. You have an ecosystem where there are generally just a couple, there are some of the fastest growing sectors of our economy are controlled by one or two companies, which is bad. Now, the question is, why is it bad? Digging it in and among itself, isn't bad, success isn't bad, but those sectors, whether it's computer hardware, social search, retail, tend to be growing more slowly now because there are no new business formation. Try and raise money to start an e- commerce site, try and raise money to start a search engine right now. There hasn't been a social media platform of any size started in the US since 2011, which is Pinterest, and this is a market that's growing 25% a year. Whereas in the US, 15% of companies used to be less than a- year- old, it's now 7%. You think, why is that bad? Maybe the world should be bigger companies. It's bad because the job creators, two thirds of new jobs are created by small and medium sized business. If you look at the industries that aren't dominated by a monopoly or duopoly, whether it's FinTech or biotech or AI, those industries are booming in terms of startups. Look, I think that how do you compete? You can't. You call your Congress person and you ask them to do their job, and return to our proud legacy of antitrust. When a company becomes an invasive species and starts killing small companies in the crib, and prematurely euthanizing big companies, you go in and you break them up. That's what we've done for 100 years. We did it with Aluminum. We got companies, we did it with railroads. We did it with AT& T. Google was born of antitrust. If the DOJ hadn't moved in on Microsoft in'99, we'd all be saying, I don't know, bang it. This notion that antitrust is anticapitalist is ridiculous. That's the argument they'll make, or they'll make some nationalist argument that the Chinese are coming for us with our AI weaponize warriors, and we have to have big companies to fend them off. There's no evidence that the national champion strategy ever works. Just look at Air France or Bombardier in Canada. Look, I think a key component of capitalism is antitrust, and these companies are... Washington is literally being overrun. Anyways, you asked how you can compete? The answer is you usually can't. There'll be some well- publicized victors. Lululemon's doing great, Ford is doing great, Walmart's holding in there, but retail generally speaking has been a terrible place to work or invest over the last 20 years, unless you're investing in Amazon.

Michael Rivo: I wanted to talk a little bit about just at a high level, how ripe for disruption higher Ed is Scott, around the idea of schools as a luxury brand and not bringing access. I think what's interesting right now is many companies have announced that they're no longer going to require a college degree for lots of different roles, and they're opening up opportunities there. We do that with Trailhead, which is our free platform where you can learn Salesforce skills that lead to great jobs. Do you see that as a trend? Do companies need to get more involved in training? What are the big changes that you see coming, or needing to happen in higher Ed?

Scott Galloway: I'm part of the problem. Higher Ed has morphed from being the greatest upper lubricant of mobility in the history of mankind. I was raised by a single mother, lived and died a secretary, our household income was never more than$ 38,000 a year, and I'm here with you and I'm economically secure because of the grace and generosity and vision of California taxpayers, and the Regency University of California. When I applied to UCLA, it was$1, 200 a year in tuition, and the acceptance rate was 60%. I had to apply twice. The remarkable Scott Galloway had to apply twice to a college, where the acceptance rate was 60%. This year, that tuition has gone up 30 fold, not 30%, 30X, and acceptance has gone from 60% to 9%. There's more kids from the top 1% of income earning households that'll get into 30 of the top 100 schools and five of the obvious, and the bottom 60%. You're 77 times more likely to get into an elite university if you're a top 1% income earning households. We have slowly but surely, everyone and as you can imagine, very popular at NYU, but I think every university or near every university chancellor, head of endowment, or tenured faculty, ask themselves the same question over and over. How do I reduce my accountability and increase my compensation? The way we've done that is by figuring out how to become the inaudible of higher Ed, and take our acceptance rates from 60% down to 5%, and that creates this cartel where the second tier schools get all the runoff, and can charge the same price, so kids get a Hyundai for a Mercedes price. We've raised tuition 1400% in the last 30 years with no discernible increase in outcomes, administrative costs and salaries. What we pay ourselves has exploded. The outcomes are no different. It's just tuition has gone up, and we've created this cartel where we've essentially become the enforcer of the caste system. The thing that Salesforce can do, the thing that Tesla is doing, Google's doing, Apollo, which is the big hedge fund I talked to premier today. The best thing these companies can do to really foment change, is to stop fetishizing people with college degrees, and to say that two thirds of our kids are not going to end up with college degrees. If Susie gets into MIT, rock on Susie, that's great. But two thirds of our kids won't even get a college degree. Is the American dream, just a dream for them? I think the short- term best thing great organizations and platforms like Salesforce can do is to say, “ Okay, it needs to be slightly easier to get in here without a college degree than it would be to bring a gun or meth to work." You literally cannot enter the halls of these organizations if you didn't get a college degree, and usually it's a college degree from an elite university. That is the hall pass, the security badge for the greatest wealth creator in history, and that's the US corporation. Is it 10%, is it 30%, is it 40%, is it developing a series of skills based, as opposed to certification based tests, that say this single mother didn't have a chance to go to university of California, Los Angeles. She went to junior college, she had to drop out, but guess what? She's very good at what she does, and she's taken these courses that are totally focused on CRM. She doesn't have time to take philosophy at Yale. She has to take care of a kid. She has to get done. She works hard, she's efficient, and we're going to create an on- ramp into the incredible careers we have here. We're never going to ignore the kid from Stanford. Those kids are incredible too. They deserve what they achieve, but there's got to be an on- ramp to the great American experiment for the two thirds of our kids that aren't going to get a college degree. Anyways, I think we have to drop the fetishization of the college degree, says a university professor.

Karen Mangia: I was going to say one of the most illuminating experiences of my life is having a bachelor's and a master's degree from traditional four year universities, and then choosing to go to community college and earn a degree as a professionally trained chef through a program where you can also earn a certificate. What was so illuminating about that, as I thought through that experience and the application to the world we live in today is, when I get right down to it, I was better prepared with a skill and a trade, to go out and do something hands- on, leaving that community college experience than I was leaving with an international business degree from a four- year university.

Scott Galloway: Vocational training is something that the US doesn't do as well as Europe. We've just got to recognize two thirds of our kids are not going to get a college degree. Have we given up on them? But that inaudible from Dartmouth, she's going to be just fine. She's going to be just fine. It's the kid that goes to junior college for two years, for whatever reason. Most of us aren't remarkable at 18. Most of us just aren't remarkable. There are some remarkable kids, more power to them. I can mathematically prove to each of us that our children, the 99% of our children are not in the top 1%, and we've got to find a path for people other than the children of rich people, and what I call the freakishly remarkable from lower and middle income households.

Michael Rivo: In these conversations with companies, what are you suggesting that they do? How can we make an impact here?

Scott Galloway: One, start recruiting. First thing is start recruiting from" second tier schools" to start figuring out skills and certification based hiring plan. What Google's doing with certificates is really inspiring. The IT certificate, two thirds of the people who've taken it don't have a college degree. The average salary of someone who gets a certificate is$ 62,000. It's 50 bucks. It's not a four year thing. I think it's six months. I'm trying to do the same thing in my startup, section four, we're trying to democratize elite business school education, 1% of the friction, 10% of the costs. We need to unbundle the university experience and say, I just don't have the time, the resource and the inclination to go hang out at college for four or five years, but I want to understand CRM. If Salesforce said, we have a three, six, 12 month program where you can become, you have to show a certain amount of innate ability around math, logic, critical thinking, whatever it is, some testing. But if you show those skills, we have a cheap and cheerful means of getting CRM certified, and we're going to hire a bunch of those kids, and we're going to treat those kids as if they have a bachelor of arts. I think you guys do something similar. I know you have a bunch of programs around that nibble around the edges of this.

Michael Rivo: We do Trailhead.

Scott Galloway: What's it called?

Michael Rivo: It's called Trailhead. It's the fun free way to learn Salesforce, and you can get certification and build a career, and there's some fantastic stories. I think it's just scaling it. It's just more of it, and it's exciting that Google and others are, Microsoft, I think is doing some of this too, but yeah. Thinking about a new way of reaching all of those people and validating it, I think it speaks to what you were saying, Scott, where the elite brand around college as a whole, if that's only one third of the population, and then of course the top tier schools. If you're a kid looking at that and you don't get in, you just feel what's the point? I think elevating some of this vocational training and making that more validated is important.

Karen Mangia: Salesforce also has the Pathfinders program, which is apprenticeship focused. Think about taking some people who've done a few classes and then giving them some hands- on experience, vocational school style in some hands- on technology experience as a pathway into that profession.

Scott Galloway: 10 years ago, I got calls all the time from parents, with kids applying to college. 10 and 20 years ago, the majority of the calls were, " My kid got into Wisconsin and UCLA. Where would you tell her to go?" Now, the calls I get are, " My kid did everything right. Got great grades, great SATs, captain of the lacrosse team, applied to seven grade schools and got shut out. And the whole house feels shame and rage right now. Literally, like what on earth are we supposed to do?" Stanford has trebled its applications. It gets three times the applications, it's increased its endowment 10 fold, hasn't increased its freshmen seats by one. Harvard is sitting on the endowment that's the size of the GDP of El Salvador. They let in 1400 kids. They got 55, 000 applications, they let in 1400, and they could let in 14, 000, and they're like, “ Well, that would hurt the brand." No, it wouldn't. No it wouldn't. When UCLA was letting in 60% of its applicants, that brand was strong enough for me to get a job at Morgan Stanley. The brand was strong enough for me to get into another brand Berkeley. The notion that somehow it's going to dilute their brand quality, these are all thinly veiled excuses for my colleagues to get drunk on luxury and say, “ We're Chanel? We're not public servants." We need to embrace big and small tech, double the capacity of our great state universities. The Ivy league, write them off. They're luxury brands. They want to feel good about themselves through exclusivity. They're going to double down, in my opinion, they're a lost cause, I think we should tax their endowments. They're not nonprofits, they're luxury brands. Where you move the needle is our great public universities. Ohio state will graduate more kids this year than the entire Ivy league combined, Florida state as well, University of California, Cal State, University of Texas. You take these programs, and I think you do a grand bargain at a legislative level, and you say, “All right, we'll increase your budget by 20% if you increase your enrollments by 50%." Using a mix of small and big tech, and the dirty secret that profs have is that if we took the right 50% of our courses, and I'm not saying go and put them online, I'm not saying doing a may synchronously, you still want live lectures, but you could dramatically expand the capacity because right now the excuse they make, my class used to be 160 kids maximum capacity, because that was the biggest classroom at NYU. Now, my classes are 280 kids, but we're still charging them$7, 000 or 1.9 to$ 6 million to hear me do this for 12 nights for two hours and 40 minutes, which if that sounds morally corrupt, trust your instincts. At some point, we should be expanding. Michigan should have 60, 000 students. Berkeley should increase its freshmen seats by triple the population growth. We need more good, not freakishly remarkable kids getting into great schools. It's one, figuring out on- ramps for kids who don't go to college, and two, it's taking our great public schools and giving them the same opportunity I had. The good news is as you get older, you get empathetic. The bad news is as you get older, you get empathetic, and you start hearing the collective cries of these households. I feel as if we hear this collective scream of tens of millions of households saying, " You know boss, you got your shot. Where's mine?" I think about when I was applying to school, and my major skill was I could make a bong out of household items. I got in the 80th percentile on the GMAT and I had a 3.1 GPA, and college was supposed to be about how do we take good kids and turn them into remarkable kids. Now, college is how do we take remarkable kids and rich kids and turn them into billionaires. It's not America, that's the hunger games. I think we need an absolute switch in the zeitgeists of our society. That America is about giving everyone a shot to be in the top 10%, not about turning the top 1% into the billionaires. I think universities are the tip of the spear here in terms of a total loss of the script becoming morally corrupt, deciding that they are no longer about giving people remarkable futures, and we're drunk on luxury, and I feel university leadership has really let America down. How's that?

Michael Rivo: Got to tell it like it is. Go on, go on.

Scott Galloway: I haven't had lunch. It's clear I'm angry.

Karen Mangia: Go ahead.

Michael Rivo: All right, Scott, this has been fantastic. Thank you so much for joining today.

Scott Galloway: Let's keep fighting the good fight.

Michael Rivo: Big fans. When I mentioned that you were going to be on, everybody was very excited.

Scott Galloway: What a thrill. That angry guy. The angry guy who curses all the time.

Michael Rivo: Can you piss him off a little bit? Crosstalk.

Scott Galloway: That's easy to do. That's not a tall order. All right, guys, I'm going to hop. Good to see you.

Michael Rivo: That was professor Scott Galloway, speaking with Karen Mangia, vice president of customer and market insights at Salesforce. Thanks for listening today. If you like this episode, be sure to subscribe wherever you get your podcasts, and thank you to Shannon Duffy, EVP of product marketing at Salesforce for joining us at the top of the show to chat about Salesforce connections. You don't want to miss it. It's happening June 2nd, this year. Head over to salesforce. com/ connections for all the information. Thanks again for listening today. I'm Michael Rivo from Salesforce studios.

DESCRIPTION

Scott Galloway, professor at NYU Stern, multi-time founder, best-selling author, and host of the Prof G Show, joins the podcast with Karen Mangia, VP of Customer and Market Insights at Salesforce. In this wide-ranging conversation, Scott and Karen share their perspectives on the long-term economic and social effects of the pandemic, the ever-evolving relationship between consumer and brand, and the rapid acceleration of digital. Plus, hear a deep dive with Scott on the death of higher education, company-driven training programs, and what he learned about healthcare while trying to schedule a vasectomy.

If you enjoyed today's episode and want to hear more great interviews with top business professionals, be sure to check out Marketing Trends, the #1 marketing podcast. Twice a week you’ll get to hear interviews with industry-leading marketers, including CMOs, CEOs, and thought leaders in the field. Go to https://marketingtrends.com/ to subscribe and learn more.