Internet Security and Building Trust-A Conversation with Taher Elgamal

- 0.5

- 1

- 1.25

- 1.5

- 1.75

- 2

Michael Rivo: Welcome back to Blazing Trails. I'm Michael Rivo from Salesforce studios. And today I'm joined by my podcast partner, Rachel Levin. Welcome Rachel.

Rachel Levin: Thanks, Michael. It's good to be here as always. And something that's been on my mind, do you feel secure Michael.

Michael Rivo: Secure? I'm not sure why you're asking me that.

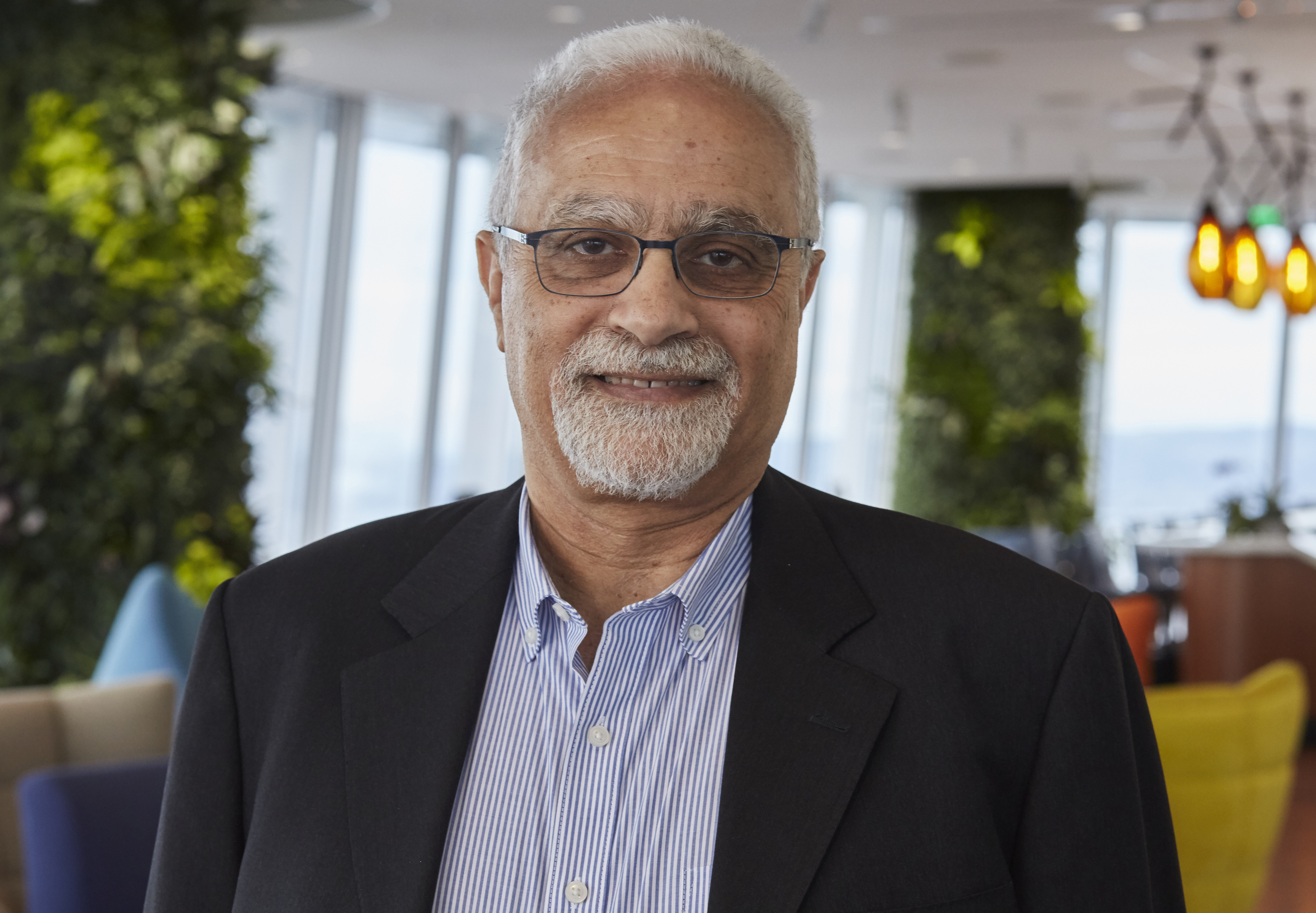

Rachel Levin: No, no, I'm not talking about your self- confidence. Although we can go there, but no I'm talking about cybersecurity. Yeah, and the conversation that you had with Salesforce's CTO of security, Taher Elgamal, cryptographer and who many consider to be the father of SSL?

Michael Rivo: It was a thrill to chat with Taher. He's been at the heart of Silicon Valley from the early days, and he built SSL with a team at Netscape that opened up commerce on the web.

Rachel Levin: Wow.

Michael Rivo: Think about that. That's kind of a big deal.

Rachel Levin: Yeah, yeah.

Michael Rivo: It's a pretty big thing. And it's still running on billions of machines today. Talk about an incredible impact. So we had the opportunity to talk about the evolution of cybersecurity, how business leaders should be thinking about it in the future. And it's a unique opportunity to hear from one of the true trailblazers of the industry.

Rachel Levin: Yeah. I know I learned a lot on that talk. Especially, I love that story that he told that when people first got their debit cards more than 20 years ago, they used to write their pin number on the back of the cards. It's bananas.

Michael Rivo: Well, there is a lot of human factor that goes into security and Taher touches on that in the conversation. So let's just jump right into it, to my conversation with Taher Elgamal, legendary cryptographer, Marconi fellow and Salesforce CTO of Security. Taher, Welcome to Blazing Trails.

Taher Elgamal: Thanks, Michael. It's really great to be here.

Michael Rivo: Okay, wonderful. Well, to start, I did see when we were doing some reading that we have the same birthday, August 18th. So it's a little early, but happy birthday to us coming up.

Taher Elgamal: How about that?

Michael Rivo: We're both Leos here. And on that note, I would love to hear about some of your growing up in Egypt, about your parents, what it was like there and where you fell in love with math as a child.

Taher Elgamal: Yeah. I fell in love with numbers before I fell in love with math. My father was a high level official in the Egyptian government for quite a long time. He actually ran the health department for the country for several years. And he was difficult to find, but that's the case for all busy fathers. But I actually fell in love with numbers, first. My parents tell me, I don't actually recall that myself, but my parents told me that when I was like four or five years old, I picked up the Cairo phone book and added all the phone numbers together. And if you know anything about Cairo, it's not a small city. There's quite a few phone numbers in that thing.

Michael Rivo: Right.

Taher Elgamal: And then apparently I did some statistical analysis of why there were more eights than nines or something crazy like this.

Michael Rivo: Wow.

Taher Elgamal: So numbers were kind of very therapeutic for me. And when I grew up, I analyzed it as numbers never changed their mind, actually. It's a beautiful thing. People on the other hand, change their mind all the time, every second sometimes. And when I went through school and college and so on, it was obvious that math was my favorite subject. When people ask me," What was your favorite subject at school?" it was actually algebra. And there are very few people that have that answer to that question.

Michael Rivo: Right.

Taher Elgamal: I found algebra to be wonderful.

Michael Rivo: And just to get back to that topic, and that led you to Silicon Valley and to Stanford in the early eighties, in the early days of computing. And I would love to hear about some of that history at your time, getting your PhD at Stanford and what it was like in the valley in those days.

Taher Elgamal: Oh, it was a wonderful thing. I came in'79 and I came to get a PhD. And I wasn't exactly sure what topic it was going to be. And I kind of found Martin Hellman who's the person who invented public key cryptography out of all subjects. And we chatted and I liked the subject. But I was studying my favorite topic, which is actually in mathematics called number theory. Number theory is a very large part of mathematics. And I took a whole bunch of classes and it just fulfilled my dream because that's what I grew up loving. And it turns out, I still love it until today. So with the help from Martin Hellman, I was able to study cryptography and write a thesis that became famous and graduate and build a career in cybersecurity. But the Silicon Valley was very different 40 years ago. It was full of fruit orchards. You don't see fruit orchards anymore. There were Stanford and Hewlett Packard and National Semiconductor, and that was it. Apple was barely starting and it was very different. The whole Silicon Valley was basically centered around Stanford, which is a good thing for me at the time. So I got to know people, I got to meet people at Stanford, very, very smart groups. I got to learn about the country. I came as an adult, I was in my mid twenties when I came in and it was like popping in movie. What I knew about the US at the time was basically from the movies because people watch US movies all over the world. So that was an interesting thing. I learned how to speak English. I was taught written English in Egypt, but I learned how to speak English by talking to people and became an integral part of the valley. I've been in the valley longer than most people as it turns out now, because most people have not been here for 47 years. I basically technologically grew up with it.

Michael Rivo: And could you feel at the time that the valley was on the precipice of something big happening or was that later when that feeling came?

Taher Elgamal: I remember a conversation I had with my boss at Hewlett Packard. So my first job right out of school, when I finished my PhD, was in Hewlett Packard labs, in parallel to here right across the street from Stanford. So it was kind of the same neighborhood. And I had a conversation with my boss at that point, so that's 40 years back. And I told him," Hey, look, I think the internet is going to take over the world." And we were connected. The internet existed, by the way at the time. There was no web or HTTP or any of the stuff that we take for granted these days. But inaudible we sent emails and we understood what connectivity meant. And he reminded me after the IPO of Netscape in the mid nineties, he actually called me and said," You were right 15 years ago," or whenever it was. He said he remembered that conversation, which is kind of hilarious actually.

Michael Rivo: Well, it took a little while to get there. And you were right at the center of it, working at Netscape in the early days of the dot- com era. And that's where you developed SSL and you have this wonderful moniker of the father of SSL. So tell us about that a little bit, those days at Netscape and developing that.

Taher Elgamal: I do not actually know who invented that father of SSL thing. It just sits in the web for some reason. I get called that. But you're saying it took a while for us to get here. Actually, if you look at the pace of change in the society, and I mean the global society, it's the fastest change ever in 25 years. We live in a completely different world from just 25 years ago. We take all of these connectivity things for granted. SSL played a central role in securing things, which is sort of fun to see. You work on things because you feel good at the time. You're never going to be able to predict that there's going to be billions of copies of something that you worked on being used in every single machine in the world, which is kind of funny. It is true today. And this father thing, although I did not call my myself father of SSL. I have two kids that my wife and I love.

Michael Rivo: Not including SSL.

Taher Elgamal: Not including SSL. But I think that the reason that it was named that because they actually nurtured SSL until it became a standard. I didn't just write something or write a paper or a patent. We did write the patent at the time at Netscape. And we had a whole team that built these real detailed protocols back and took it to the world. But I actually took it to the IETF and made sure it became an industry standard. And we convinced Microsoft that it was the right thing to do, to agree on a single protocol rather than build multiple ones, and it just became what it is today.

Michael Rivo: I'm curious if that process is similar now of developing of protocols. At the time, it seemed like there was such a spirit of everybody was in trying to grow the internet. Everybody had a view into what the potential was, and maybe there was more collaboration. Would it be the same process to develop a new protocol now, as it was back then?

Taher Elgamal: Actually, it feels like not exactly what you're saying, because even back then, there were other protocols that people were working on that even the IETF itself was trying to standardize. But people were still building and shipping things with their own proprietary stuff. If you look at the payments industry, for example, which obviously we did e- commerce in the early Netscape days. That was sort of the number one goal, that was the target. The payment industry has so many protocols, it's hilarious. The only thing that even the payment industry agreed on is use SSL for internet payments. It's the only one thing that the entire payment industry ever agreed on, which it was because it was available, it was there, it was in all browsers and all servers. And because it was the one standard everybody implemented. It was inter- operable and it was easy to use. But there has always been the desire to build proprietary things for control. And I don't think that was different back then from now, actually. I think there has been, even back then, a desire to build a proprietary thing because you think you're going to control an ecosystem. But clearly controlling billions and billions of machines talking to each other with security built in would not be done by any one entity. There's just no way. It doesn't matter how big the entity is. So I think now we recognize the value of the collaborative effort. And people still remember.

Michael Rivo: Yeah. The open standards really opened up that whole opportunity. And since then, you've been involved with securing global networks at scale for many years now. And you're leading that effort along with Jim Alkove here at Salesforce. What do you see the challenge is ahead in the security space?

Taher Elgamal: There are some dirty secrets in the answer to this. In the early days we looked at how do we use this internet, it's an open network, how do you use it to do e- commerce? And e- commerce to us was conduct a transaction over this open network. What does that mean? Because an open network means that anybody can see everything or people can even modify things if they can't see it. So we said we have to hide these transactions from the open network. That's where the SSL idea came from. It was a company effort. Unfortunately, what happened after this, SSL became a standard and successful. And the world believes that we solved security. Security is done, let's build e- commerce and they just moved on. And we did not, at the time, analyze threats that might be coming afterwards very well. So we analyzed a particular number of threats that have to do with an open network. And we'll let that the business grow. And then a few years later you discover that people are attacking the corporate network. So you can get people's transactions sitting in databases. That's nothing to do with the open network. They did not actually attack SSL itself, they attacked something else. And then they got innovative. I do not know exactly who came up with the ransomware idea. It's pretty innovative. You just get ahold of some machine or some group of machines and you tell the owner," Pay me a dollar and I'll give it back to you," sort of thing. So the attacks, the threats grew out of proportion faster than the controls could be done.

Michael Rivo: Yeah. I just saw a headline today, the G7 meeting is today and that it used to be nuclear security that was the topic of conversation. And now it's cybersecurity. And I think we're seeing all these ransomware attacks. In fact, I tried to book a ferry for an upcoming trip and I couldn't book it online because the ferry company had been attacked by a ransomware attack. Now, every organization is a digital organization and has a digital front door. How should senior leaders be thinking about these security issues and communicating with their teams about that?

Taher Elgamal: There is the good, there is the bad and there is the ugly. The good is everybody's realizing the nature of the threats. Now they're becoming infrastructure. You can't go to the ferry, right? This is not a transaction that somebody stole. This is an infrastructure issue. Or you can not get gas in your car when you're driving in the East Coast. The bad is companies and agencies and entities are coming up to speed on how do I protect myself as a business or as an agency. So each entity is building knowledge about how do I protect myself? The ugly is we forget that it's actually a global issue. This is not a company issue, it's a global issue. And we will not be able to solve this until we cooperate. That has to be a level of collaboration between entities, globally, for us to make this new ecosystem risk level sort of correspond to the risk level of the normal human being life that we're used to for the last million years or whenever human race started. The problem with the high connectivity is that it is making the risk much higher, percentage wise, and a lot closer. In the old days, to attack someone, you had to cross borders and bring people. There was a lot of physical activity. Now you can conduct these things just by sitting at home. So it's a very different world. I'm glad that G7 are talking about it. I hope they work together. I hope we work together with all of them and with others because the level of connectivity is just higher than what we can protect globally until we actually know how to work with each other correctly. And it's not going to get fixed now by somebody doing one or two things, it's going to take a number of years, maybe decades to actually get it done correctly.

Michael Rivo: And when you think about the level of connectivity, and then you start to bring in what's happening with IOT, what's happening with peer- to- peer and 5G, and the connectivity is exploding and has been for years. And it continues to, with so many connected devices. How do you think about an overall security protocol as this grows so much? How should companies be thinking about that?

Taher Elgamal: Yeah. So as a community of human beings living in different places, we have not come to a realization yet that anything we built and connect into this connected world is both value, but also produces risk. Companies that build IOT devices do not consider what they are building to be part of the risk, although everything that is connected is part of the risk. You hear of attack using IP cameras to attack things. The camera didn't do anything, but it doesn't have any protection. So it actually launches the attack from the camera, because if the attacker can find their way through different connected nodes on this network, the level of attacks as much bigger than anything we're used to. So I think we need to come to the realization the conclusion that any and everything we build needs to understand that it's connected and it needs to take into consideration what it is protecting and what it can get access to that can hurt us.

Michael Rivo: Yeah. I think about that in my own life now when I realized with all these connected devices, wait, you're bringing in another access point into your house. How do you think about that when you're putting things in your house? What's your thought?

Taher Elgamal: It's a good point. And there is the immediate and there is not so immediate thinking. So the immediate is if you connect your door, for example, which a lot of people now do to the network, somebody can open your door sitting in their house. That doesn't sound like fun. And so this is even the immediate thinking. The not so immediate thinking is somebody can use your fridge and everybody else's fridge to attack some other thing. Nobody's thinking of this and the fridge companies who literally don't think of that. But they're all nodes on the same network. They're all connected to each other. There's no two networks, it's all one network. And if any group of nodes are available for an attacker to get ahold of, you're going to see amazing things. So we are not impacting even from the first immediate things, as in, can someone in fact, open your door over the internet, sitting at their house? It takes a lot of thinking to make that product. But certainly people are not thinking of the bigger story.

Michael Rivo: Now Salesforce's security and trust is a number one value here at Salesforce and securing our customer's data is paramount to what we do. But we're not in the consumer security business. How does Salesforce connect to some of these larger global issues that you're talking about?

Taher Elgamal: Salesforce has access to a lot of customer data, you're absolutely correct. And if you look at everything that gets done in Salesforce, it's all centered around protecting customer data. It's actually one of the number one goals, just protecting customer data. And the growth of Salesforce is exactly one to one corresponding to growth of customer data. And when that happens, it's not just the growth of the data, it's the nature of the data. There's more data, but there's also more sensitive data that is more important. So the focus at Salesforce on security is huge because it's a core part of the business. You're right, trust is our number one value. And to me as a security professional, trust means protecting customer data. That's what I tell the CSOs that I talk to every single day. I talked to customer CSOs all the time. And that's what I tell them that for a security professional to tell another security professional what trust means is that we will protect your data and we will put that at the highest level of protection because we have to. So we built a really good security program, the company's investing a lot in security. We have some of the best people in security in the company. But as a company, we're always looking into, how do we give back? This is part of Salesforce. This is how the company was built. Now, giving back does not mean hurting Salesforce security because that doesn't actually get anywhere. So we partnered with the World Economic Forum, for example, and give away our security training to them. If you go to the World Economic Forum site, you'll find security training material that we just donate it. We give away for free, it's available to every single person in the world. And the notion is the more security aware people in the world, the better the whole cybersecurity situation is going to be. It's going to take a worldwide activity, which obviously Salesforce is always part of, but we need a lot of collaborations. We need a lot of governments, even governments that don't exactly see eye to eye, we need these people to talk to each other. So as a corporation, we're always ready and willing to give back and contribute and participate, but clearly building a worldwide resilient network is something that needs a lot of people to participate.

Michael Rivo: I've taken the security training as a Salesforce employee, and I can tell you that it taught me a lot of really simple things that I hadn't really thought of before that are just very basic rules. And in some ways, it's how to think about security. It's beyond passwords and two- factor authentication and just some very simple things. How are maybe we thinking about this the wrong way, or what are some of the really simple pieces of advice that come out of that training that people should know?

Taher Elgamal: It's being aware. Physically, if somebody were to drop you in the middle of a city, your eyes are going to automatically look around and see, is this a suspicious place that there's weird things happening, or this is a safe place for me to walk around? And as a human being, you're going to actually behave differently, depending on how you sense the place that you physically are at. It's hard to do that in a network because you actually don't see exactly where you are. So awareness is very important. Knowing which sites somebody is clicking on, it's sometimes not easy to detect if a particular location in the internet is actually safe or not. So we need to collectively develop the awareness of this. And part of that is what we teach in these classes that you said you've done, just don't click on something you don't know.

Michael Rivo: Right.

Taher Elgamal: It's just the simplest things. People still share their passwords. Remember, when ATM cards, when debit cards first showed up 20 something years ago, people used to write the pin on the back of the card. And then the banks were on our case. People, people, the whole point of a pin is that you don't write on the same card because you want the access to be correct. We have to change the way we deal with technology to be able to arrive at a safe place.

Michael Rivo: And when you think about that for a whole organization, what should be top of mind for CIOs and CTOs right now? What are you hearing in the conversations that you're having with leaders of enterprise companies? What's top of mind for security right now?

Taher Elgamal: The threats are not exactly known, are unexpected. Although, technology professionals at large always understood the nature of what a ransomware attack could or could not be. For example, we did not anticipate all of this, but we understand technically what goes in. The fact that we have to protect our businesses, our organizations, our agencies from attacks that are yet to come is actually the number one issue because we do not know what the attackers are going to come up with. There's a lot of machines and computers and processes and cloud services and everything connected to everything. And the adversaries are very smart at finding weaknesses. Finding a weakness in one computer in the sea of computers can actually yield to an issue that could eventually yield to a breach that is harmful. So the attacker has the edge. The attacker needs to find an entry point and then follow it while people who are protecting needs to protect the entire thing. So it's actually not a fair game as far as that goes. The attackers work with each other. They're actually extremely connected, they build on these tools. They continue enhancing the tools and the people who are protecting their own companies collaborate, but to a much less degree. So when you're thinking top of mind, the top of mind is can somebody utilize some weakness someplace and launch attack that I'm not aware of and how many layers of defense and protection and detection do I need to build to optimistically prevent an attack, but at a minimum detected early enough so it doesn't cause real harm. We all know this industry, there's this new thing in cybersecurity that we all call zero trust. And what it means is you have to assume that some bad person, some adversary, found their way through and they are actually in the middle of a network that you care about and you want to minimize the impact of that.

Michael Rivo: Taher, this conversation is going great. It's super interesting. The question I have when I think about that, where you've got a group of attackers who have the advantage and you're constantly on the defensive, it's almost like being a defensive back against a great quarterback, offensive team. What's that feel like? You've been in this role for your whole career really in this defensive position. What does that feel like to be there all the time?

Taher Elgamal: On one hand, it's kind of really fun because you're solving difficult problems, which is what in the technical world we strive for. We all want to find solutions to difficult problems. Every once in a while, you wish that people worked together a little bit more to make the situation better. Every once in a while you wish that the infrastructure was built in a somewhat different way that is easier to protect. But at the end of the day, we play the cat and mouse game, we're good at it. And you protect against these massive amount of attacks by building layers and layers of protection.

Michael Rivo: I know this comes out of your love of cryptography, that's your field of study. I don't know a whole lot about it. I would love to hear some of the fun stuff that you've worked on, or just tell me a little bit more about it as a field. And beyond security, how are you still involved with it right now?

Taher Elgamal: People did ask me," Why did you get in cryptography?" And my answer to that question is cryptography is the most beautiful use of mathematics I've ever seen. It's just absolutely gorgeous mathematics. It changes with time. It's not a fixed time. So it forces you to continue to think and change, and you want to apply it in different ways so that you can protect important things. But it teaches you how to think differently. And the simplest way, as an example of thinking differently is, what I tell people, people come to you and describe the product, and I listen to startups and people starting things all day long, and they're describing how beautiful the thing is. And the vast majority of people will listen and contribute and love the conversation. But a cryptographer will think how this would fail, which is the opposite thinking, because over the years you train your brain to think differently, which I think it's a needed skill. And I think security people will continue to be needed and the numbers will continue to grow. Everybody tells me," We need more security enabled people. We don't have enough, the world does not have enough." That is correct. Cryptography is an example of a use of mathematics. I do not know, I was extremely lucky maybe or whatever, but it's really awesome to think through.

Michael Rivo: Well that love of cryptography and all the work you've done over the years has led to you recently winning the Marconi prize, which dates all the way back to 1975 and is featured some of the most important people in the industry have gotten the award, Tim Berners- Lee and Larry Page and Sergey Brin and your PhD advisor, Martin Hellman as well. Tell me a little bit about the award.

Taher Elgamal: It's magnificent to be recognized, obviously, by the industry that you are part of for some four years. It's a wonderful feeling. The Marconi society itself was started by the granddaughter of Marconi, who's the person that invented the radio way back when. So it was actually in recognition of her grandfather. And that group is just unbelievable. Vint Cerf is the current chairman of the Marconi society. Vint is the inventor of TCP/ IP, the first internet protocol that is still around until now. The individuals who invented the cell phone. Things that we take for granted are part of these Marconi fellows. So being invited to be part of that group is a wonderful feeling. And I learn a new thing every day by listening to these conversations, because obviously people are specialized in their fields.

Michael Rivo: Well, it's been such an incredible time of innovation that you've contributed to. I've learned so much and it's changed the world. There's no doubt about that. So this has just been a wonderful opportunity to catch up and learn about your career and about security at Salesforce. So thank you so much for joining today. It was a great pleasure.

Taher Elgamal: Thanks, Michael. It's been great to be here and I appreciate the opportunity.

Michael Rivo: That was Taher Elgamal, legendary cryptographer, Marconi fellow, and Salesforce CTO of security. For more, we've got some great resources on Trailhead, our free learning platform, to help companies and individuals of all levels, develop security knowledge. Go to trailhead. salesforce. com/ cybersecurity. Again, that's trailhead. salesforce. com/ cybersecurity. And if you liked this episode, be sure to subscribe wherever you get your podcasts. I'm Michael Rivo from Salesforce Studios. Thanks for listening today.

DESCRIPTION

A decade ago, trusting a brand meant trusting the quality, consistency, and delivery of their service or product. While that still rings true today, now trust between consumer and company relies heavily on a new pillar: trusting that the brand is protecting your data.

With data leaks, breaches, and hacks becoming increasingly more sophisticated, who better to invite on than Taher Elgamal, known as the “father of SSL” -- the encryption that makes the websites we visit secure. Taher joins the show for a discussion about the past, present, and future of cybersecurity. He talks about his background in the industry, why stopping ransomware requires a game of catch up, and what should be top of mind for CIOs and CTOs today.